Unfinished

I make lists. To-do lists, playlists, favourites lists, recipes, wordlists, lists of details on my phone. The veneers of control. This writing began from list-making. The phone logging emerged shortly after my granny was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s – two years after my paternal gran was diagnosed with dementia.

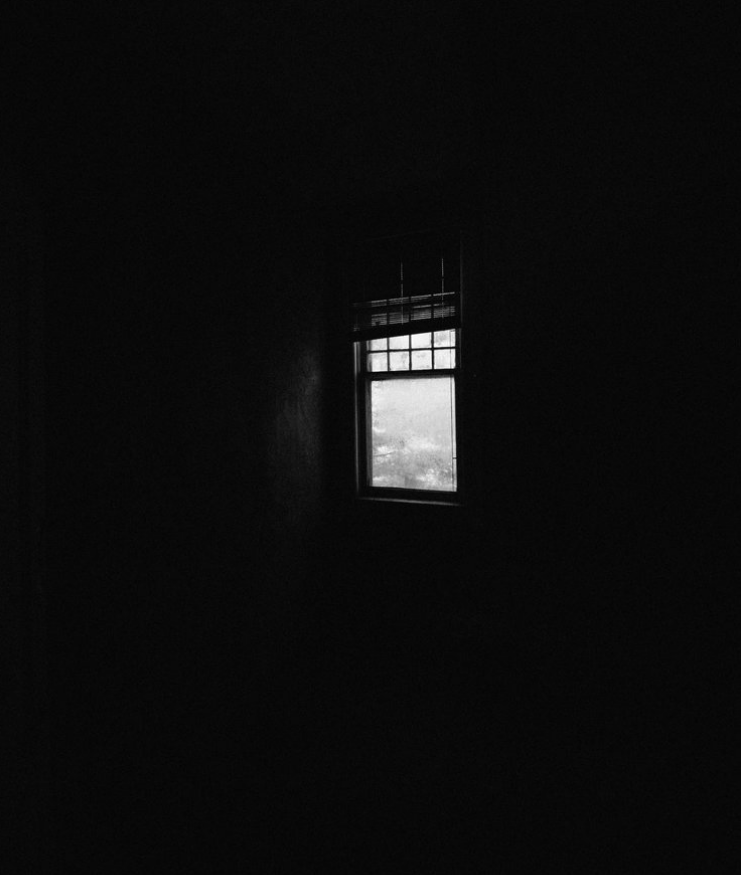

I was wading out in the ocean one day when memory suddenly seemed so fickle; the temperature of the water, the night before. I was desperate to live every minute so fully that I might never forget it. Ever since, I’ve become this ‘crazy bag lady’ of experiences; nothing is wasted, it’s all thrown in and trailed around each and every day. The practice of list-making is also the practice of attachment.

1.

Every second weekend she takes me to the cinema. She smuggles juice in her handbag, refuses to spend money on popcorn. We watch STV dramas. She drapes her bra on the arm of the chair. ‘Let it all hang south’, she says. Her car smells like Polo mints.

2.

She gives me £3 pocket money. We play ‘Snap’ and ‘Old maid’. She tells me when I’m older she’ll teach me how to play ‘Bridge’. Her fingers are long and slender. I clumsily paint her nails. I overhear her and my dad discussing the gravestone. We vacation in London and she buys me goth boots.

3.

She never speaks of grandad. Her favourite books are the murder-mystery ones. With a dose of teenage pride, I tell her this is ironic. She ignores me. Jam blisters the rim of the pot. We bake a sponge. I know she wants a second slice. She mutters something about her waist and takes my plate.

4.

I rub my hands together in the cold. She insists I get my poor circulation from her. A bowl overflowing with necklaces sits near the bed. She wears an alert button around her wrist. Sometimes I stay up at night imagining various scenarios in which she falls, and what I would do.

5.

I don’t want to sacrifice my weekends with friends. She gets dial-up. My sisters and I show her Solitaire websites. The bathroom shelf is stocked with tubs of E45 cream. She never remarries. I think about a life absent of romance for over forty years.

6.

They rescind her driving license. I trip up on her electric scooter. I call her to announce that I can finally make decent empire biscuits, or ‘double biscuits’ as she says. In the hospital, she grins at some distant point in the room. She can’t give me advice now. I comb her hair.

My own process eludes me. I do not yet wake at 6am or take regular breaks. I do not even drink coffee… The dream of the work is still a dream. The dream of my life is a dream on this page. And yet all stories are worthy of telling. I think about all the periods in my life I’ve spent doing nothing; I can call them incubations, I can call them regrets, but neither one is sufficient. It is very feasible that the most interesting chapter of my story has already happened, and that the most interesting part of me is tragedy. There is movement in every story. And my story has seen movement, yet it’s been slow. I can sit very still for very long. And now I wonder at what point this stillness will catch up with me.

What is the admission fee for a piece of life writing? There is currency in suffering. We won’t admit it but it’s true. Suffering competes for the right to write. Violence sells. Survival sells even better. I might be a champion of character, resilience; I turned out alright. Just about.

What is the admission fee? To be not alright.

When I was around nine, a girl asked me how my mum had died. We were queuing up for fizzy bubblegum bottles in the Girlguiding hall. My dad stood in the doorway, ready to collect me. The floorboards creaked as we edged forwards. I had answered this many times: ‘She was killed’, ‘she was attacked’, ‘I don’t remember.’ The reactions were usually fascinating. I made friends far easier than anybody anticipated because I traded the ‘weird past’ card. But this was the first time my dad was in earshot; I knew because I felt his shoulders harden.

‘I don’t want to talk about it.’

In this case, the interesting answer would have come at my dad’s expense. I was unwilling to pay that price. He put his arm around me and told me he was proud but I shrugged him off and got in the car. Seventeen years later I find myself devoting an entire project to the subject – perhaps because I am tired of not talking about it.

I attended a funeral yesterday. My gran’s neighbour, a close friend of my dad’s. I’m not sure what compels me to reflect on such things now. Some people discussed money, nervously, unaware of what to talk about; one woman commented on another’s Gucci handbag, men eyed the flashy cars. When the hearse pulled up there was silence. Even the trees seemed to stop moving. We shuffled into the crematorium and everyone had their arms locked to their sides, as if afraid to take up space. On a screen at the front row, photographs of the deceased showed on a loop – him on his wedding day, with his dogs, on holiday and back to his wedding day, and again.

A cacophony of sobs. Men with red faces, hunched shoulders. I have never been in a room with so many men sobbing; I have never been in a room with more than one man sobbing. I look up at the loop again and see different faces each time: in place of him are all the men I’ve known, and though my dad sits next to me squashing a tissue into a ball, I see him up there too.

I look at the coffin and try visualising a person inside it. But it just looks like a varnished piece of furniture, a long coffee table.

I have lost what I was trying to say. No clear point breaks through. A funeral is a vital interruption. So it will always be. Except, it is not quite an interruption to the work of life writing but rather a supplement to it. And now I am trapping myself in my own self-referential loop…

It is difficult to be at a funeral and not to think about God or mothers or global emergency. At least, it is difficult for me. I have a feeling of

love as imperative,

no longer sunny or romantic or fixed in place.

Love;

the feeling remains, remains, remains. Occasionally I wish it wouldn’t.

1.

‘Right, tiger’, he says, and carries me up to bed. When the radiator goes cold he drains it, sits on the floor breathless. A cigarette dangles from his mouth. My sisters joke that he was born with the moustache. He claims he liked it at fourteen, kept it ever since. His shirt smells like engine oil.

2.

We have tinned ravioli and ‘soldiers’ for lunch; I can’t seem to say soldiers, so I say ‘shoulders’ instead. He sleeps past noon. I dread asking for help with my arithmetic homework. He raises his voice when I get another sum wrong. On her birthday we go to Tesco and buy flowers. His eyes fog up.

3.

My gran comes over every Sunday to clean the house. His room is crammed with washing, old rags, used tissues. There’s discarded packets of Zopiclone, throat lozenges stuck to the bedsheets, mugs of cold coffee. He blasts Meat Loaf in the car.

4.

I tap my foot, shoot him looks. He’s been talking about cars for over twenty minutes; my friend’s parents look tired. He helps me remove my black nail polish with paint thinners. We watch documentaries about plane crashes, offer up our theories. ‘It’s always the rivets!’ I laugh.

5.

I like listening to his stories about cattle farming; waking at 4am to start the milking, playing cassettes in the tractor cab. Every year I encourage him to return to it, to buy a few acres. One night he starts crying in my room, gives me a hug. I freeze. I wait with him in the GP surgery.

6.

He converts an old oil drum into a fire pit. I politely sip his homemade wine. The lines of his hands are etched in dirt, sawdust. His fingers are calloused. I learn to listen between the words. For Christmas I make him a copy of mum’s photograph and place it on the mantelpiece.

*

Death is unfixable.

A proclamation. As I typed these words I was shot up with a sense of the unfinished; that such a phrase necessitated a companion. It was missing something. I read it over again and again, from left to right and left to right…. there is always more to death. Always. It occurs to me that this work I engage in now is an inadvertent commitment to disseminating such truths.

Yes, there is always more to death. It may be unfixable but

loss is fixable. By this I mean to suggest that death is unfixable but loss is not – loss is neither permanent nor fleeting. Good writing taught me that. The ocean taught me that. My granny taught me that. It is possible to repair enough so that life moves again; it turns and turns.

I do not wish to present myself as a healed figure, to make an example of myself through a kind of ‘survival memoir’. I don’t recommend ever declaring the ghosts unless they’re ready. I don’t recommend writing them unless you’re stubbornly bound to, and even then it takes more than courage – it takes desperation.

A word document. Dream thoughts. English text, tapping keys. The following words appear:

perhaps only imaginative sense can avoid grammatical sense;

perhaps in absurdity, truth speaks….

A young woman tries simultaneously to create, get lost and make sense.

-

Zoë Frances is a writer and interdisciplinary artist, and a graduate of the University of Dundee MLitt Creative Writing programme. Her work strives to vanish the divisions between artmaking and living, while exploring voices of trauma and grief.