Goyder’s Imagined Space

A place can change you. A place get under your skin, make a home of your body. A place can challenge your sense of what it feels like to be a sensing, sense-making being.

I’m still trying to understand how Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia changed me. It’s a strange place, inconceivably remote and unrelentingly hot and I lived there for three years in my early 30s. I was an accidental economic migrant, only intending on visiting my sister for a couple of months but staying on in part because I had landed a job that was—both financially and professionally—better than I could hope to gain back home.

After an early wet season rain shower, photo by the author

But I also stayed because my family needed me. And because the place flooded my senses in a way that still courses through me several years after returning to the UK.

Darwin was where I watched Octonauts in my niece’s bedroom as my sister gave birth to my nephew in the room next door.

Darwin was where I re-learnt what it meant to care, as an aunty, as a burnt-out community worker.

It was where I burst into tears in my first ever writing workshop.

Where I burnt out again and began to learn—really learn—how to recover.

Where I learnt how small I was, and how big.

Darwin was where I first heard the phrase Mercenaries, missionaries and misfits. It’s used most commonly in the context of development and aid work across the globe, but while I lived there I heard more than one Darwin resident use it to describe the many incomers who populate the NT. Which one was I?

I can’t shake the connection I made with the NT, which must be why I’ve spent the last year researching for a story about a place-name that exists in both Dundee and Darwin, and what that dual-naming might tell us about our relationships to land, culture and identity. In the midst of that work, I learnt the story of how Darwin came to be.

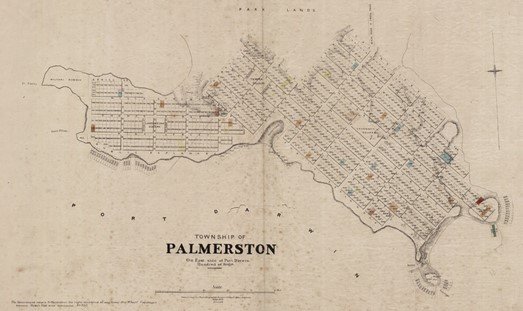

The Liverpool born, Glasgow trained surveyor, George W. (no relation) Goyder was tasked with surveying and establishing the settlement of Palmerston on Australia’s northern coastline after a couple of failed attempts before him. Goyder barely conceals his excitement in his first official report back to Adelaide a few weeks after he disembarked from his ship, the Moonta, “Notice may at once be given to land-order holders to select their lots… I am very pleased with what I have seen”[1]. The hypothetical land had been sold off in lots long before Goyder had set sail, so there was an urgency to his project which must have held sway over his opinion of the place. He saw everything he had hoped for amongst the heat-hardy corkscrew pines, the paperbarks and the soupy heat; he saw a ‘first class country for large stock’, timber ‘suitable for nearly all purposes’ and fertile soil ripe for cultivation under the ‘rank, uncropped vegetation.’ As if there were something grotesque about a plant which had not already been felled, a tree that was not yet timber.

He saw an un-made city. All he needed to do was put some streets onto it.

Goyder had landed in a place called Garrmalang, home of the Larrakia people for uncountable generations. In contrast to Goyder’s party, Larrakia people did not—and still do not—distinguish themselves ontologically from Larrakia Country. Before European settlement, they sustained themselves by way of a sophisticated economic philosophy that allowed them to thrive in a place that to this day is a barely hospitable landscape in the eyes of most incomers.

Although the settlement of Darwin was less immediately cataclysmic for the aboriginal population than some of the earlier encounters in the south of the continent, Larrakia Country was desecrated all the same, it’s custodian’s survival reliant on their quick-witted diplomacy and ability to assimilate into the creed of their new neighbours.

The shape of Goyder’s vision was an uncompromising and ever-rising line, on a collision course with the Larrakia’s vision of an ever-replenishing circle.

And his line continues in the visions of leaders, misfits, mercenaries and missionaries in the city they now call Darwin, once Palmerston. Contemporary Garrmalang is a place overrun with ‘rank, uncropped’ air conditioning systems and artificial shade structures. It is a military and ‘natural resources’ outpost heavily reliant on a vulnerable road, rail and air freight system connecting it to the southern cities and to its closer neighbours in South East Asia. Is this what Goyder imagined?

The fact that his settlement clung on where several other attempts on this region had been abandoned is, according to his culture’s own logic, is proof of Goyder’s sound judgement and first-class training. What Goyder held in his mind as he looked out over that beautiful country of towering storm clouds, capricious only to the uninitiated, was a proven model. For him and the investors who backed him, it made perfect sense to duplicate the ordered grid system of the Adelaide streets here, or really anywhere, and to do so in a matter of weeks without much thought to what already existed. At the time there was every reason to believe his claim that ‘sooner or later it will turn out well’. Although Goyder’s plan had its flaws and Darwin’s history has been a far from smooth line upwards and onwards, many of the original streets remain and the city has persevered.

And I love that place, with its vivid sunsets and high-contrast inequalities, the sensory deluge of its markets and its painful histories. That love is knotty and irreconcilable, something I pick at in my writing because I think it’s attached to some fundamental knowledge of myself and my place in an unjust and damaged world. Reading Goyder’s reports fills me with a sort of dread-in-hindsight; he was certainly a mercenary, and a missionary for colonial expansionism. He was ruthless in his vision. His ignorance and hubris are at times painful for my 21st century sensibility to contemplate. But I want to understand him, and the traces of his plan that sit ghostlike behind my own and that of the culture I inhabit.

Township of Palmerston on east side of Port Darwin, Hundred of Bagot. 1870 Frazer S. Crawford, Photolithographer, SA Surveyor-General's Office, Adelaide. National Library of Australia. nla.obj-232289421

Because I think all humans have a desire to see our visions made real, whether they be political, domestic or artistic. Creative expression—the ability to fold one’s own desires, predictions and imaginings into our concrete experience to generate something new—is, in essence, our ecological niche. But no vision, however radical, comes from one mind, and our sources cannot be reliably traced—there is no better school for this lesson than a couple of years working in community development in a culture that is not your own. Our independence of vision is dependent on others, and many of those indiscoverable others will harbour ulterior motives that shape us in ways we cannot know.

Where, in my own imagined spaces, creative visions, surveys and plans are those ulterior marks, those histories of injustice that I claim, on my visible, cognisant surfaces to be resisting?

And where are yours?

Ellie Julings

[1] GW Goyder, Northern Territory Survey Progress Report, 2 March 1869 Available online: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2618538509 Accessed 25/07/2022 All further quotes from Goyder from this source.