“things a creative essayist should know:

Faber-Castell watercolour pencils and

why certain people avoid direct eye contact and

how to braid and

stitch things and

how to speak to strangers.”

— Essaying

“Writing Come Undone”

Lara Luyts

Turn the page,

see how it’s made.

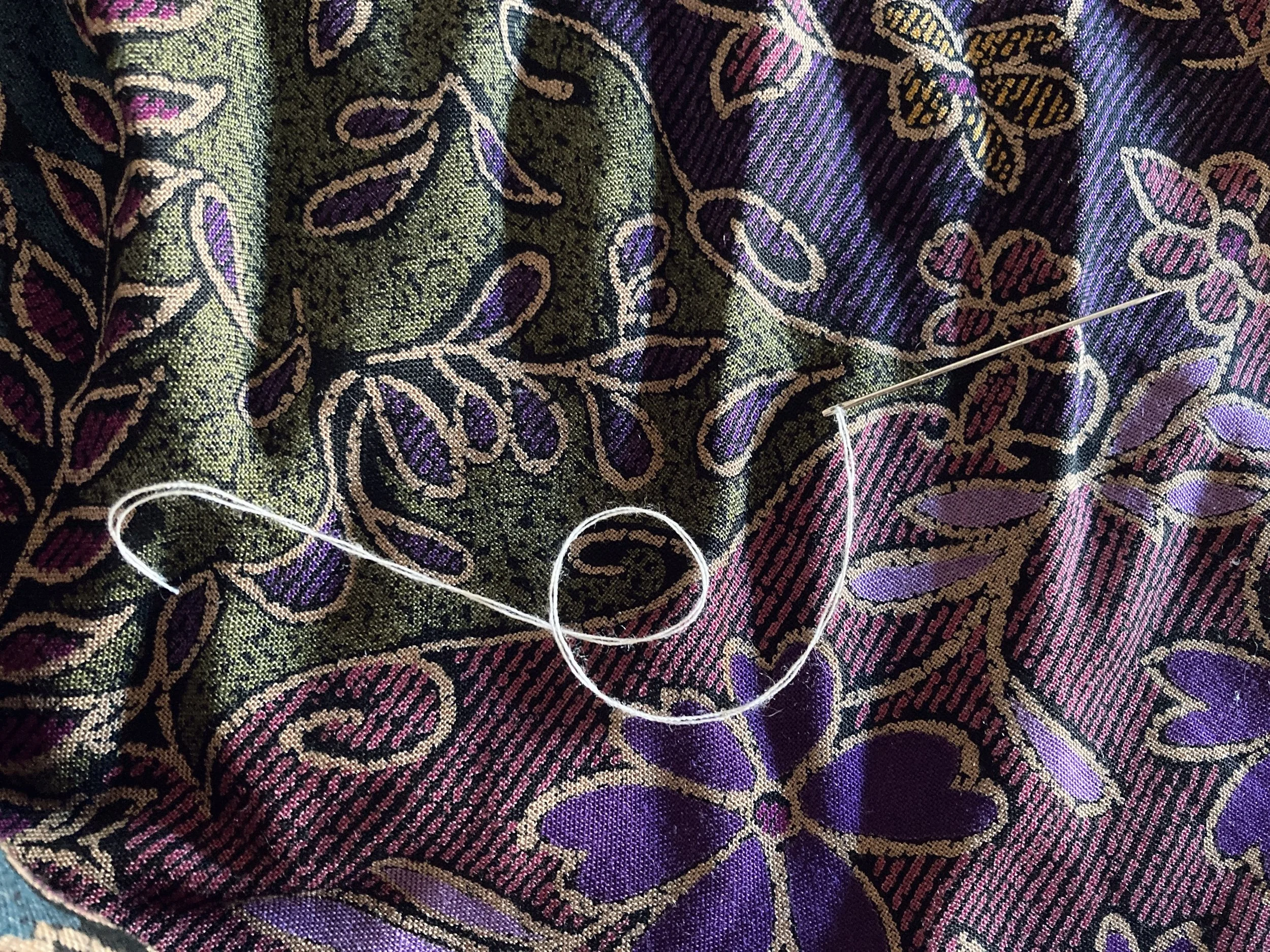

Trace the stitches Pull the thread

and see and watch

what they reveal. as it unravels.

Crawl inside the skeletons of words

unspoken.

See what holds them together,

love them from the inside out,

treasure their secrets until

finally

they become your own.

Drawing, a passion I had as a child, required more patience than I possessed. What frustrated me was how hard it was to fix mistakes. Pencil drawing only gives the illusion of second chances; you can erase whatever line is out of place, yet faint traces remain. A patch of your drawing is smudged, grey clouds staining paper. You draw over it but that one spot, the evidence of your mistake, will always be glaringly obvious.

What about writing, then?

When typed out, any text can be a final draft. Typos, rewrites and repetitions are erased and replaced without a trace. Or is that only how it appears? Can a text, once polished, be undone? It seems impossible. An author can release the first draft of a work, draw back the curtain and let us peek through the windows of their mind, but even then, readers remain passive spectators. In The Allure of the Archives, Arlette Farge describes an exception:

Historical writing should retain the hint of the unfinished, giving rein to freedoms even after they were scorned, refusing to seal off or conclude anything, and always avoiding received wisdom.1

I was sceptical about this at first. My impatience always has me reaching for conclusions. I read it again and this time… I feel enchanted by the idea of the unfinished. Why should we reserve this concept for historical writing? I am reminded of Charles Simic’s Reading Philosophy at Night, an essay I disliked because it felt untethered. I struggled to understand it, to follow Simic as he wandered from topic to topic, never still long enough to reach a conclusion. It bothered me when certain fragments drew me in, only to leave me behind, lost in unknown terrain. It took a few rereads to realise that was the point. What I criticised is what makes the essay unique. It requires me to search and make my own connections. Simic laid out the pieces to a puzzle and it’s up to me to put them together. Frustration morphs into intrigue, which leads to curiosity, where do the limits lie? Simic hands the pen to me as reader; I can finish his thoughts with mine.

I want to see the stitches in writing, to pick up my needle and contribute to the tales. I want others to do this with my writing, discover how it changes over time, unravel all its messiness and tell me what they see. ‘Show me,’ I’d say as I hand them my needle. I want readers to see the blurred shapes, to find their own stories in my mistakes.

Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013)

“a form of control”

by Sarah Axt

‘Exercising control is quintessentially what it means to be human.’1

When writing, all was fragmented and incoherent. I had too many ideas for one thing and too many things for one idea.

How to stitch all parts together,

I wondered. A failed attempt; losing control by writing about control. I looked elsewhere for help.

My friend integrated haikus into their work; where ideas could be rigid, precise, and condensed. Its form gentle, provocative, where words came alive effortlessly. If I tried hard enough, I would befriend my fragments, at least direct their form. I liked playing hide and seek.

we are one, today –

I chase you like ideas

here, you hide, once more

There was a butterfly in church today. We played hide and seek. At times I could see it, at times I could not. The insect reminded me of the ebb and flow of writing. How I knew it was there, not always in peripheral vision, but visible, nevertheless.

Where?

The butterfly bounces from window to window, desperate for light. Like ideas, held up by rumination. A whole forty-five minutes, I sat there with a paper cup, hoping it would make its way towards me. Occasionally, the butterfly would simply sit still, exhausted from bumping into glass repeatedly. I knew it wasn’t at peace, it was only recharging energy for another attempt to freedom; its body caught, bumping against impermanent objects.

sit still in time, no

stroke of pen can harm you here,

behold filtered wing

I never really liked butterflies. When I was twelve, my family and friends went into a butterfly house. It was tropical. A botanical garden. Picturesque and beautiful, until the insects started landing on me. First one, then three, then dozens. They must have liked something about me. I felt they were everywhere, their tiny legs all over my skin. Uncontrollably tickly. I stood still for a while, then ran. Their touch sends a shiver down my spine now.

My mind tickles like that. A million receptors, firing at the speed of light. One thought jumping over another. What is writing but that? A circus of ideas. Exciting and terrifying; uncomfortable, thrilling. When do you lose control? At times, I flee when I think there is nothing left to write. Left to right, nothing meaningful to find.

I never really liked forcing creativity. How unnatural, to push something so intuitive. How silly to write only when our senses are tickled, an itch to be scratched. What is writing but loss of control? Creativity requires mastery, as well as liberty. I vow not to run when inspiration is sparse, or receptors drive me mad.

can you do a thing

but wait and know the key is

pressing back again

Butterflies die if you touch their wings with your oily, human fingers. Would I have to leave it behind, I wondered? I kept chasing after something I wasn’t sure I could hold. ‘Poetry is the result of restlessness of imagination’ – fluttering, fixing ideas.2 The comfort that there was room for uncertainties in unknowing, ungrasping. Restlessness and uncertainty both challenged a form of vulnerability. I was vulnerable in the waiting, and yet I knew how it gave way to writing about a billion beautiful interactions. Like a butterfly chase.

I caught it in my paper cup in the end. I brought it outside and freely it flew.

into cold air it

flew, its numbered days never

known outside church walls

My hands never touched it as I never grasped all that writing could be. I had let go of ideas, repeatedly. Restlessness was a form of my ambition accompanied by a guilt that could haunt me. ‘We are likely to learn more than we planned on, in the course of making. We think we knew a thing. Now we know it differently.’3 I thought I knew the butterfly when what I saw was myself.

Creating consistently, not aiming at perfection and immediate satisfaction, entailed for me to embrace the unknown. How would I know what ideas would last? My mind stumbled upon doubt as I deleted line after line. Note after notes formed drafts. I let ideas bounce around in echoing halls, narrowing minds; tried to contain it with haikus and changed their form entirely. Editing was on-going. It always would be, as time, surroundings, and understanding of a thing changed.

The process was the butterfly.

Jenny Diski, ‘Otherness’ in What I Don’t Know About Animals (London: Virago, 2012), p. 60

Carl Phillips, ‘On restlessness’ in New England Review (2009), vol. 30, no.1. Available at: <https://www.nereview.com/2013/12/12/on- restlessness/#:~:text=Carl%20Phillips’s%20reflection%20“On%20Restlessness”%20appeared%20in %20NER,the%20result%20of%20a%20generative%20restlessness%20of%20imagination> [accessed 23 October 2022]

Ibid

“The End, and Then Beginning”

by Ida Valimaki

What is essaying?

Thinking on paper, thinking in real time? Conversations with yourself, with other writers, with your readers? Reworking and rewording every paragraph until they sound just right? And then starting from scratch, over and over again, until you’re finally finished?

Essaying is thinking and talking.

Thinking and talking are moments. Moments are intimate, immediate.

Essaying is an imitation of moments.

Thoughts are intimate: they are a writer’s mind, how they see the world, how they work. Thoughts are a writer’s whole being, their skills, their potential. We are nothing if not our thoughts.

Thoughts are immediate: they are urgent, here now and then gone, never replicable. And even if you were to return to your old thoughts, they would’ve shifted in the time you were gone. They will always look slightly different.

Conversations are immediate: they only happen in moments. Words in the air, ideas exchanged and formed. Even if you were to write it all down, that transcript could never be truly faithful; conversations don’t occupy space, but time. You can’t use words to record time.

Conversations are intimate: they only exist for the people present in the moment. They are the thoughts of those people meeting one another. They are what we think for.

An essay has no immediacy. It exists outside of time, in exact records that never change. The words an essay is made of will never evolve beyond what they are on the page right now. You can read it a thousand times, come back to it years later, examine and analyse it, and yet it never changes.

An essay has no intimacy either. It is to be read by the masses. It is performative and planned out. Everything revealed has been carefully considered, and nothing is said that the world can’t know about.

In both thinking and talking there is only the present. They cannot be accurately replicated or recorded; nothing can be added or removed lest it becomes a new thing entirely. They only truly exist once. An essay has no present. It is not thinking or talking in moments, it doesn’t have moments. An essay has a past: what the writer has done. The thoughts and conversations have already happened. It is the result and record of thinking and talking. It is the end. An essay has a future: what the reader will do. It will continue to exist in the thoughts and conversations of its reader. It will inspire new thoughts and new conversations; it is the beginning.

The thinking and talking of essays happen outside the paper.

Thinking happens when we write. When we draft and craft our ideas and sentences, when we notice something that feels wrong, and we push ourselves to find out why. When we form our arguments and develop our examples. Thinking is the process of writing, of putting ideas into words. And, in the end, we have an essay showing that thinking without all the side-lines and cul-de-sacs. An essay is thinking made coherent and understandable, it is thinking perfected.

This, I think, is what Philip Davis meant when he quoted John Henry Newman saying: “Writing [...] is the representation of an idea in a medium not native to it.”1 What are ideas if not thoughts building on one another? Immediate and intimate moments. Writing moves moments outside of time, to be shared. Writing takes pictures of the moments, always leaving something out. Writing about moments never produces moments.

Davis expands: “Even as writers raised their pen between one sentence and another, there was always implicit, underlying thinking going on before, within, and after each separate unit.”2 There is no writing without thinking – the process of writing is thinking. The thinking makes writing a moment, intimate and immediate. We pour ourselves on the page, over and over again, and in that moment nothing else exists; only us and our thoughts. Writing in moments never produces moments.

Writing can inspire moments.

Thinking happens when we read. When we run into a sentence that sends us down a spiral we hadn’t explored before. When we run into a sentence that summarises something we’ve been trying to understand and can now link it to new, better, bigger things. When we run into a sentence that is so blatantly wrong, we can’t help but argue with it. When we come back to a text we once read, or never finished, and it is now different somehow, and it leads us to different places. Thinking happens when we’re done reading and still can’t pry our minds off the essay.

“An idea at its deepest has more than just statable content.”3 It holds the promise of more, the potential for more, and we must be the ones to find it. We are the ones meant to free it from the page it has been strapped to, find the thoughts in between sentences and work out what we can do with them. We do it by reading, by thinking while reading, thinking about our reading.

It all leads to inspired moments.

Conversations in an essay happen on multiple levels. The writer is talking with themselves through the page. They are talking with other writers, responding to their ideas, deconstructing their arguments. They are talking with their readers, explaining their thoughts, leaving a space for responses. The reader is talking with the writer, listening to their thoughts and then forming their own in response. Maybe writing them down. They may talk with other readers, share their opinions. Conversations happen before an essay, in the writing process, and after it, while reading.

“Speaking, as it goes forth into the air, is also the hope of being spoken to, in return.”4

An essay, then, is a medium of conversation, thoughts put on paper in the hope of getting a response. In the hope of generating thoughts in the reader, in the hope of getting them to continue the conversation. To write an essay is to hope for a response, per Philip Davis. This interaction, the conversation of an essay, the sharing and generating thoughts, is essaying.

Essaying is not an imitation of moments: it is a recording of them, it is inspiring them. It is the intimacy of thought and conversation that allows you to know someone recorded on a page for immediate access no matter where or when you are. It allows you to get close to the writer’s mind, close to the moment of writing and the immediacy of it. Your response, your thoughts, generate a new kind of intimacy between you and the writer, one instigated by the writer and reciprocated by you. And that moment of reciprocation as you read is immediate and inescapable. If you’re not thinking, you’re not reading. And if you’re thinking, you’re talking with the writer.

An essay is both thinking and talking.

We make it a moment.

Philip Davis, Reading and the Reader: The Literary Agenda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) p. 28

Ibid, p. 28

Ibid, p. 45

“I want to write essays”

by Jeannie MacLean

In the 1580s, Sir Philip Sidney wrote:

Loving and wishing to show my love in verse …

Biting at my pen which disobeyed me …

My Muse said to me ‘Fool, look in your heart and write.’1

Around 400 years later, Carol Ann Duffy wrote:

In one of the tenses, I sing

an impossible song of desire that you cannot hear.

La lala la. See? I close my eyes and imagine the dark hills I would have to cross

to reach you. For I am in love with you

and this is what it is like or what it is like in words.2

I understand the urge to write. To use words creatively rather than simply as a means of communication. Feelings, emotions; the disturbances of life which prompt us to write. I find it hard to anchor myself against gusts of emotion, to keep the boat steady enough to find such words.

I want to write essays –

I want to steer the ship and not be overwhelmed in rough seas.

Between the lives of these two poets, I hear Virginia Woolf’s voice, asking us to look outward and observe life in all its detail while watching a moth crossing a window:

Watching him, it seemed as if a fibre, very thin but pure, of the enormous energy of the world had been thrust into his frail and diminutive body. As often as he crossed the pane, I could fancy that a thread of vital light became visible. He was little or nothing but life.3

Observation and reflection might be what draws me to essays. Continuous prose which engages in conversation and draws the ‘curtain around us.’

Fragmented essays which allow the mind to inhabit spaces and consider, to find other words and responses.

Woolf’s essay, published posthumously, is short. Small like the moth and minutely examined, taking the reader away from the concerns of the day. Focusing on the struggle of such a small creature to stay alive, we are temporarily ‘shut in’ with the moth, invested in its struggle.

A fragment of time, caught in words. There is much space around the tininess of this incident for the reader to inhabit.

I want to write essays:

To converse with the world and find myself reflected in my observations.

To celebrate and colour the experience of being alive in this complex world.

To find the spaces between the words where the magic happens.

Lia Purpura, in her fragments, gives an insight to the writer’s mind, how it plays with words even when the attention is elsewhere. Like a background hum, the words gathering and sorting themselves. Becoming.

I remember thinking “it looms over us,” then saying aloud “looming over” and then, to better myself, to sharpen my sight, when it flew I said, “the air of the loom.”

I was walking my son to nursery school when I saw how the notion forming was poised, with hawklike curves, with fox-like silence.4

Purpura gave us two fragments - encounters that brought words which have circled and formed something unique to her.

The piece is short – six fragments, closely observed, with five white spaces between. Like eating a carefully crafted meal, it is good to pause between courses and consider how each mouthful builds on the sensuous pleasure of the previous one and to feel satisfied by the complexities of flavours at the end.

I want to write essays –

To explore form and write memoir in ways which go beyond straight narrative.

Continuous prose with thinking space.

I turned to Chris Arthur’s essay, ‘Table Manners.’5 I wanted to know why this essay spoke to me, what Arthur had done to draw me in again and again.

First, I read it aloud: I could hear my voice sounding the words from the page. My mind admired the cadence and rhythms of the words, but I was still an observer. I wanted to be an inhabitant.

I set about copying it, word for word, mark by mark. I used pencil and paper and took my time, feeling my way through the structure like an archaeologist. I got my hands into the soil of it.

There is no waste in this essay; each image and phrase earns its keep. There are spaces for the reader to inhabit.

I want to write essays because I am not interested in tying arguments up neatly or reaching conclusions. I feel like I have stumbled into a world where exploration is the thing.

Mary Oliver puts it like this:

Like the knights of the Middle Ages, there is little the creatively inclined person can do but to prepare himself, body and spirit for the labour to come - for his adventures are all unknown. In truth, the work itself is an adventure.6

Sir Philip Sidney, Astrophil and Stella: The Major Works (Oxford’s World Classics: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Carol Anne Duffy, ‘Words, Wide Night,’ in Collected Poems (London: Picador, 2015)

Virginia Woolf, ‘The Death of a Moth’ in The Oxford Book of Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 410

Lia Purpura, ‘Red, An Invocation’ in On Looking (Kentucky: Sarabande Books, 2006), p. 59

Chris Arthur, ‘Table Manners’ in Words of the Grey Wind (County Down: Blackstaff Press, 2009), p. 87

Mary Oliver, Upstream (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016), p. 27

“How To”

Callum Gavin

In Things I Don’t Want to Know, Deborah Levy writes, “it’s exhausting to learn how to become a subject, it’s hard enough learning how to become a writer.”1 I dismantle the mirror self into shards and put it back together unrecognisable, but I am learning how to be a subject, how to be an essay. To dissolve into the mirror and disappear between the words, but still find my way back.

Deborah Levy, Things I Don’t Want to Know (London: Penguin Books, 2018), p. 40