Being an Essay

Arrowe Park Hospital, Birkenhead, 1988.

When people ask me where I was born, I tell them I was born in Liverpool; it’s easier. Everyone knows Liverpool don’t they: The Beatles, the Mersey, Cilla, Clive Barker, two historic football clubs. It was at the heart of the industrial revolution, which also means it is inextricably linked with the Transatlantic slave trade perhaps more than any other major British city. Birkenhead? Well, Elvis Costello and Alex Cox spent time, and Birkenhead Park was a major influence on Frederick Law Olmstead when he designed Central Park in New York.

“Karen???”

“Ka. Lum.”

It’s 1988 and the receptionist is attempting to register my birth. In a town near Liverpool, no one has heard the Gaelic chime of ‘Callum’ before. My mum first offered ‘Sebastian’, but that was a singing crab in Disney’s 1989 animated film of The Little Mermaid. My dad said ‘Jack’, but my mum once had a dog with that name. Callum it was to be. That receptionist would have no such issue now, as a snowfall of parents in the late-eighties and into the nineties had similar ideas. I can now scarcely enter a public space without hearing someone calling out to me only to turn around and find another Cal(l)um answering the call.

*

Jacques Lacan theorised about the mirror stage, a stage in human development whereby an infant recognises their reflection in the mirror, triggering a sense of self-othering and a confusing of subject and object. I stare at the mirror, and through it to the clean white page or blank screen beyond. I was the story in the mirror, then on the screen and on the page. As I got older, the stories grew bigger. I told stories that I was exploring uncharted jungles and planets; that I fought monsters; that I did brave things; that I wasn’t the kind of person afraid to speak up in class or join in on the playground; that my fears and anxieties didn’t often root me to the spot.

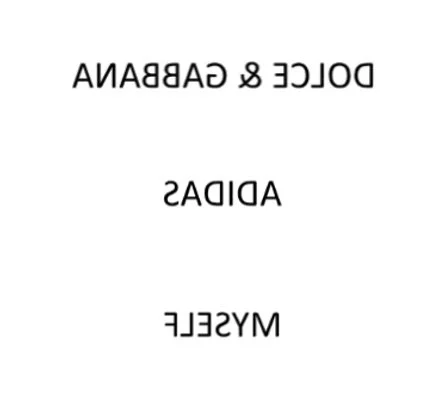

I think about the mirror stage as a carnivalesque hall of mirrors distorting and twisting the person I see trapped and multiplying in ceaseless shimmer. Me and not me. The ‘me’ who exists in the world and in the minds of those who know me might not be the ‘me’ I transfigure into words on the page. However, we are so used to seeing ourselves reflected in mirrors, screens, and shiny surfaces, that we accept that this is what we look like to the world observing us. Yet, there is a horizontal reversal at play, most obvious when we wear a shirt emblazoned with a logo:

We forget this though. When we see photographs of ourselves, images instantly recognisable as us to family and friends, everything is just a little bit off… as if the world has ever so slightly tilted off its axis and only we feel it. "One person is really like three people. The person you think you are, the person other people see, and the person you really are."[1] The mirror, the photograph, and the thing just out of view, the one you might come within glancing distance of when you write.

When I was younger, I didn’t consider this dissonance within much. I cared about appearances then, the shiniest and most forgiving reflections; that people thought I was good, that they knew that my behaviour was just my youth/the alcohol/the coke/my depression (delete as applicable). I’m not who I appear to be, but sometimes what you appear to be is all there is for other people to see. To paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, I am what I pretend to be, so I must be careful what I pretend to be.[2]

*

In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes, “our house is our corner of the world.... it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.”[3] Yet, Carl Sagan’s version is not quite so cosily domestic, the “cosmos is mostly empty,” a vast cold vacuum, “a place so strange and desolate that, by comparison, planets and stars and galaxies seem achingly rare and lovely.”[4]

As a child, home was also defined by negative space—the unknowable vacuum—as much as it was by the material safety of objects. Sun rays split through windowpanes and dust waltzed about in the space – they moved faster if you burst through the beam. Under my bed with The Lion King duvet set, was just as dark, and out there the pale granite graze the skyline and souls are squashed into every square foot, and the blazing windows and streetlamps silence the moon and the stars. Our flat was on the top floor of the tenement, there was one floor between us and the ground; the stairs were encased in beige, fraying linoleum, the black banister hugging the wall so tightly that that six-year-old me couldn’t have the simple pleasure of sliding down it. The door at the bottom, which let in the world when we allowed it, had a translucent pane of glass turning that world grey and distorted from inside. The light refracted through glass and scattered in the close but never reached the place under the stairs.

Under the stairs was negative space. No higher than four feet, no wider than five to crawl in. Once there was a broken bottle and I knew what that was. Once there was an unbroken needle and I thought I knew what that was. Dark and empty, an absence which felt distinctly like a presence.

The space under the stairs was the subterranean brought above ground, the hidden made visible, the unconscious exposed. You didn’t have to burrow into the grass of a manicured lawn outside like in the start of Blue Velvet[5], the gardens here were concrete. The world opened up beyond my flat into the neighbourhood, to the other boys and girls who floated in empty space in and through my little universe. The boy with the golden curls sometimes ate his dinner on his own out on the landing, and sometimes my mum would give him dinner, even though she and his mum were not friends. The boy with the missing front teeth—an exposed, twitching nerve—would fight you over nothing, cry when nothing seemed sad. The girl next door knew all the swear words, even the ones about sex that we were thought too young to know. Sometimes we wouldn’t see her for days or weeks.

When I was thirteen I left. We moved to a place with more negative space, but we found more stuff to fill it with. It had more grass outside and more darkness at night. I opened my front door, and the world came rushing in. No liminal space filled with cracked linoleum and cavernous crawlspaces. I always had half my mind on a life away from here and so I moved. I probably said goodbye to people in my close but I don’t remember. As the old neighbourhood began to recede in the mirrors on my mum’s car, I only looked forwards, through the clear window, where the new neighbourhood would soon swell.

Later, the boy with the golden curls let out a silent scream as he leapt into the darkest of spaces between the bridge and the river, he was found all twisted and blue miles from town. The boy with the missing front teeth crawled through blood and sand in wide open spaces overseas; I hear he still has trouble sleeping. It’ll take a much bigger war to mess with my sleep. The girl next door spent some time in a cellar not much bigger than the space under the stairs but infinitely scarier. I don’t know where she went after that. I did better drugs in better neighbourhoods where the trees reached higher than the granite and the kids drank Buckfast and White Lightning in the name of irony. The police never came around there much. Everyone I know now just sees a therapist. In Giovanni’s Room, Giovanni tells David, “You don’t have a home until you leave it and then, when you have left it, you never can go back,”[6] and when I am sitting in my mum’s car again, in my memories, I watch the neighbourhood trapped in the mirror, and I know I can never go back. I ask her to slow down anyway. If only for a moment. Just a moment.

*

In black screens, you can only see the faint spectral outline of your reflection, as if every frame of every image becomes trapped in your head as you dissolve into the screen and the line between what you observe and what you are begins to blur in a way that your young mind is unable to fully comprehend.

September 2001, I watched, along with everyone, as three-thousand people died live on television. We watched more people die across infinite screens; some we were instructed to care about more than others. Of course, war and death were nothing new, but this was the moment in time I became aware of things outside of my direct line of vision. Yet, bombs never fell near me, and violence, no matter how horrifying, was always kept from me by the glare of a screen I could only barely catch my reflection in.

*

In ‘Five Ways of Being a Painting’, William Max Nelson writes, “there are many ways to separate yourself from yourself. Whether intentional or not, this self-alienation creates the possibility of returning to yourself.”[7] I know that I must shatter the image in the mirror, find the words in the jagged shards and reassemble them before I can make something whole, and recognise myself again. Find the familiar in the unfamiliar, and the unfamiliar in the familiar, in the reflected image and the spaces between the shards you create, the self in those written words and those inarticulable feelings in between. Nelson suggests, “being a painting gives you an existence in both the inverted world and the familiar one. It displaces you through alienation and renewed attention.”[8]

Imagine you are walking down a street, not a new or unfamiliar street, but a street you walk down every day. Maybe you live or work on this street, or maybe it’s your favourite place to take the dog. You know this street, know to walk around the loose bit of paving the council still hasn’t fixed without looking, know it’s a twenty zone and it’s a quiet street, so you don’t need to be that cautious crossing the road; you know that evil ginger cat will be sitting in the third window on the left glaring at you. Now imagine one day something is different, the side of the street you normally walk on is closed: they’re building…. something. You go to cross the road, but the machinery is so loud that you can’t rely on your hearing to know if a car is coming, so you look both ways and you see the road for the first time in detail: the fading yellow lines and the sections that have buckled under the thousands of cars before you. On the other side of the street, your foot slips because you only ever knew about the cracked pavement on one side, and you must watch your step now. From this side of the street, the little ginger cat does not look so evil. The roofs on this side of the street are different you notice, and you stop for the first time in a long time. Under one roof, some words are inscribed in the brick, but you can’t quite make them out. You can see a year beside the words. This side of the street is old, and history was happening here long before you or your ginger friend were here. You feel dwarfed by the street and its age; you feel part of an infinite continuum. A whisper barely audible between two deafening howls of past and future. Alienation. Renewed attention.

When I write an essay – when I write myself into an essay – I am attuned to the cracks in the stories I tell myself, to the contradictions and half-truths woven into the words which form in my mind, and my place, however small, within the world I inhabit. Writing myself into an essay presents me from different angles, in new contexts, from an unfamiliar distance. Nelson says of a portrait that the subject is “not really in the middle of an action but a moment between actions, an interstitial happening that does not quite rise to the level of an event. We merely see the subject resting between pearls on the string of time.”[9] Between pearls on a string. Between words on a page. Between shards of shattered and scattered glass.

I dismantle the mirrored self into shards and put it back together unrecognisable, but I am learning how to be a subject, how to be an essay. To dissolve into the mirror and disappear between the words, but still find my way back. I wonder if Karen would have had these issues.

-

The Falling, dir. by Carol Morley, (Metrodome UK, 2014) [Motion Picture]

Kurt Vonnegut, Mother Night, (London: Penguin Random House, 1992)

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), p. 4

Carl Sagan, Cosmos, (London: Abacus, 1995), p. 21

Blue Velvet, dir. by David Lynch, (De Laurentis Entertainment Group, 1986) [Motion Picture]

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room, (London: Penguin Books, 2001), p. 9

William Max Nelson, ‘Five Ways of Being a Painting’, in Five Ways of Being a Painting and Other Essays, ed. by Rosalind Porter (Devon: Notting Hill Editions Ltd, 2017), p . 12

Nelson, p. 2

Nelson, p. 22

-

Callum Gavin is a third year student in English and Creative Writing at the University of Dundee.