“the meaning of your name, and a dream - a ghost story that speaks”

— Archives

Essays in ‘Archives’

“-”

by Katherine Stewart

“As I scratch, I find a dog-eared folder from 1892, rubbing shoulders with one from 1992. A photograph of a bearded man in a hat glares back at me from the first page. Twenty years in the asylum. ‘Incoherent. Dirty habits. Died.’ Where I stand was where there was once a workshop or a stable. Had he stood here too? With a pig or a horse? Did he babble like my manic patient? There was absolutely no way to know.”

Sally Swartz, ‘Asylum Case Records: Fact and Fiction’1

I don’t know what I expected from the asylum records. Probably horror stories and listed lobotomies. I didn’t expect the succinctness. An individual, their psyche, their livelihood amounting to a few words. With hindsight it makes sense, when summarising the intake, discharge, living and dying of numbered patients, there isn’t much room for “oh, and by the way, she’s a dab hand at cribbage.”

W--- ---- had been an in-patient residence for the mentally ill I don’t know how long ago. It was a strange place, shoved into a housing block with a porthole that looked out to the broken toilet, floating on cracked pavement outside the S- S-. Buzzed in, the stairs were dark and led to the sign-in sheet.

I wonder about the bearded man in the hat. Incoherent. Did he, as Swartz enquired, babble? Did he stutter, or slur his words? Maybe he spoke in rhyming couplets. Perhaps the recorder, the singular voice which informs the narrative, was simply incapable of understanding his intent. How would he have prescribed himself? His caretakers? His ‘dirty habits’ and final moments?

The only record I could access of the building’s previous function was a bathtub on the top floor. I remember it being stained, sinister, but in truth I have my doubts. All I know is that I avoided it.

Records are taken from a limited perspective.

Memory is fallible.

The ending stains my lens for the building, for the beginning, for the bathtub. It bleeds through in the telling.

The bearded man in the hat writes his name with a whiteboard pen onto the yellow sheet of laminated paper. Who’s in? Maybe E— with a heart or J— who was sometimes C—, he hears F— unboxing sandwiches in the kitchen, M—and D— are huffing and puffing in the classroom. It is yet to be seen who will blow it down. He sits at lunch in a room of bouncing knees and cheese rolls. Some of the others are bargained with to eat. Which role will he take in action therapy? H— or C— who were silent, J— who gladly talked too much, K— who said the same thing each week, M— who once led, ears sweating with a nervous titter. Probably he is none of them. They themselves were not. Once, we did music. They had us sing ‘Mad World.’

W--- ---- as I knew it was an out-patient day centre for mentally ill teens who’d stopped going to school. That’s the wool, however they or I might spin it.

I heard it closed down and I’ll admit I was glad.

Heard it reopened. Shit hurts.

Swartz writes that psychoanalysis, as if an archive in its own right, is “deeply involved in history, the telling of histories, the construction of the ‘facts’ of a life.”2 Idly, (selfishly) I wonder what notes have formed me over the years. If my file brushed fingertips with that of the bearded man in the hat, how would I be read?

The facts of a life: Incoherent-Dirty-Habits-Died

In that first meeting, before years spent on a CAMHs waiting list, they asked my parents about our family history. There was my mum, of course, who played charades while she stayed on the ward (the nurses always included One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), plus a handful of suicides, great-grandparents I never knew, all to be taken into account.

This, I remember as the beginning, though I didn’t know it all then, this and sipping Vimto in the hospital café. I don’t suppose the last part made it into the file. I forget how many years have passed, I forget the faces and never really knew the names that made their marks and comments unseen.

There were climactic nights, quiet days, one trip to A&E. When I picture these things, I imagine a tome.

One year in the bathtub. ‘Incoherent. Dirty habits. Lived.’

Maybe he drank tea.

Sally Swartz, ‘Asylum Case Records: Fact and Fiction’ in Rethinking History (2018), issue 22, pp. 289-301, p. 291

Ibid, p. 293

“-”

by Teddy Rose

My Irish great-grandmother’s father and brother (my great-great grandfather? my great grand-uncle? family is all words a-jumbled) both killed themselves. One swung; the other swam. My Welsh grandmother survived three types of cancer and still goes on. My English father is a drug addict and a narcissist. All of them are tangled within me. This is genetic fact.

“More than three hundred Southerners have died, if not in my arms, then in my hands,” Stephen Berry writes, “they are people re-dying for me as I read the reports of their coroners.”1 This is the permeability of the written word: as you read it, it becomes real. Before you see the report, the cause of death, this person is alive and kicking for you; their fate is set in ink. It dries in truth on the page. “Thus, deaths that are old news to them, who once were, are new news to me, who still is.”2

I read about people who are long dead. Two hundred years gone. Yet their loss is fresh to me. Their blues new. Faceless to me (faceless in graves, too), but here, once. Fleeting. I wonder if I’d know their faces in passing. I feel like I know them. Each a flower in my garden.

We are not our parents. Our families do not define us. Our blood does not dictate us. Read that again, slowly. Let it sink in. We are not our parents, and yet –

Childish, the note reads. Imbecilic. Argumentative and restless. Used obscene language over luncheon (mashed potatoes and stew.)

I wonder why it makes me ache – past the meat of heart and cavern of lungs to the yawning endlessness inside where all feelings seem to settle – the anger of this woman I will never meet. I wonder why it hurts so much that they would shut her away, write about her like this – another time, another time, I remind myself, but it does not take away the sting. I wonder how long it would have taken before they put me away, then.

Statistically speaking, I pass hundreds of faces in a day. I will not remember them all consciously, but my brain will file them away, store shades of their souls, secrets to be kept safe. I read once that the brain cannot picture a new face and yet I am taken aback every time I look in the mirror.

Red was my favourite colour when I was young, and angry. Before that, spring green, for rebirth. I have been shades of blue, but never in love with it. Not the way my great grandfather was, “stones good for sucking” in the river at night.3 I have always been yellow, deep down, I think. Would have died yellow if I’d tried, acid vomit on my bedroom carpet –

Imagines her uncle wishes to put a knife in her. And the solution was her incarceration? I am boiling over. I am potatoes pre-mashing, simmering and salted. Imagines.

We will never know what he might have done. Never know what hands he laid on her. The stomach ties in knots, the heart quickens – my anger curdles to something sickening.

Here: died, unrecovered. My hands shake. Paper slips between my fingers, heavy with dried truth. Died, unrecovered. A face I don’t know, a story I see a reflection of. In the silence, in the blank space between lines, she is screaming.

Died, unrecovered. She must have family out there, still – sisters, brothers, or cousins who outlived and outlasted, who moved forward and folded, procreated, pushed on. Her descendants could be dream fodder for me. The thought sticks like glue. Like honey. Like tacky mashed potatoes.

Died. I am haunting her bedside as she thrashes in white sheets, stricken with fever. Whites of her eyes, sweat on her brow. I hope it was more peaceful than this fucked up fantasy. I hope it was fast.

Unrecovered. New faceless blues. Ancestor of agony – trace your years back for someone to blame. Name written and forgotten. “Nothing but endings.”4

Died, unrecovered.

Stephen Berry, ‘The Historian as Death Investigator’ in Artful History, ed. Aaron Sachs and John Demos, (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2020), p. 53-54

Ibid, p. 54

Maggie Nelson, Bluets (London: Jonathan Cape, 2017), p. 52

Berry, ‘The Historian as Death Investigator,’ p. 56

“-”

by Callum Gavin

Human beings. Lives. Names. Patients. Conditions. Illnesses. Statistics.

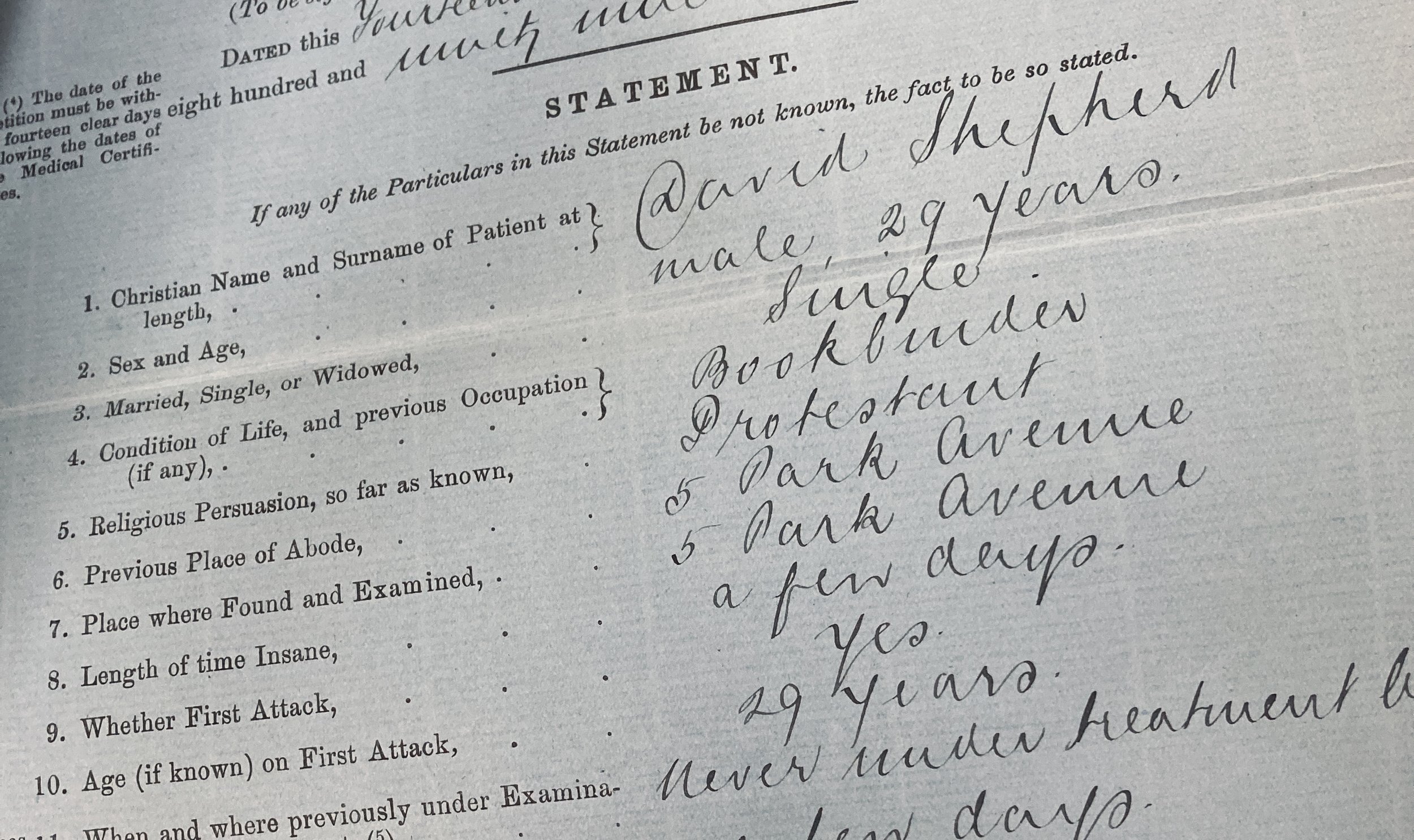

The handwriting is almost impossible to decipher, a stereotype rings true: doctors have terrible handwriting, whether in 2022 or 1922. I handle the documents with the care and attentiveness I would an infant, in sharp contrast to the lecture handouts I had, mere moments before, punched into my laptop bag. It’s not that I don’t value them or won’t read them, but those words can be printed afresh on another white and creaseless sheet, I can pluck them from the ether with a few stabs at a keyboard. These patient records may as well be carved in tablets atop Mount Sinai. The paper I hold every day, from notebooks to novels, feels like it might melt through my hands at any minute, but these patient records are different. Each page has a defined edge, each name and number carry the indentation made by the pen, and the ink somehow does not appear fully dried. They are heavy. Heavy with the weight of history.

Scavenging through the endless list of names and dates, I keep returning to the question at the heart of Sally Swartz’ Rethinking History article: “do words get anywhere near to reflecting experience?”1 I see there are rules for patients and a different set of rules for staff, food is served at the same time every day, while each patient is prescribed varying quantities of words and drugs. We seek to help, to heal; we seek to force assimilation, to make them docile and agreeable. Swartz argues, “constructions of coherent narratives so central to recorded histories obviates against representing madness, which by definition departs from rationality.”2 Lives. Illnesses. Statistics. Voices drowned and trampled while attempting to amplify them. Voices that might have moved mountains and shaped minds. Somewhere between dabbling with his first psychedelics at Harvard and sharing a cage with Charles Manson, Timothy Leary formed his reality tunnel theory founded on a belief that “each person lives in a different reality tunnel from everyone else and is personally responsible for constructing their own existential reality.”3 Like beauty, truth is in the eye of the beholder, and objective reality is a comforting falsehood. Leary took heroic quantities of acid and made some wild claims, but there is something to be said for emerging from your own tunnel, away from the darkness and echoes, and trying to catch a glimpse inside someone else’s. In these archives, there is one reality, one voice, and one way to live.

The weight of history feels heavier still in the basement of the university, far away from the chatter of students, buzz of smartphones and intrusive rays of the low winter sun. Just a stack of documents and me; the silence feels necessary, respectful, almost sacred. A booklet containing all the texts in the hospital library catches my eye, and there is something poetic landing on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.4 Sometimes, we don’t consider illnesses, especially those of the mind, to be something the person has, but rather something that defines them; a big grotesque scarlet ‘A’ for Asylum branded on them forever. Hester Prynne had to remove the weight of the ‘A’ to get a sense of how heavy it was, to grasp her freedom again.5 The weight of history feels comforting in the hands of those looking back but hangs heavier around the necks of those living it. In the patient records, there is a section for each person titled ‘General Appearance and Expression of Face,’ and John is described as having a “dull heavy meaningless” face, as if that weight had altered him physically.6 Can someone have a meaningless face?

Murray Royal Hospital, formerly James Murray’s Royal Lunatic Asylum. The name changed in 1948. They described behaviour as ‘insane conduct or morbid acts.’7 New words inscribed above a door on a building on a hill. Shifts in the preferred nomenclature used in polite circles, but labels and stigma woven into the blood trip off the tongue long after. I grew up in the shadow of Murray Royal Hospital– just ‘Murrays’ to those who lived there – in a block of council flats separated from the hospital grounds by a five-foot hedge. We wandered around the hospital grounds freely, my friends and I; there was a full-size football pitch we could play on and a beautiful garden right in the middle. Lunatic Asylum.

The hospital became part of the community’s folklore, a shifting but unshakeable component of our very language:

“You know that one about the escaped mental patient with a hook for a hand,” the story told huddled around campfires and repopularised on the edge of my teen years with sacred VHS copies of I Know What You Did Last Summer and Urban Legend being passed from kid to kid.8 9 “That happened right here. In Murray’s. No, I swear on my maw’s life it did.”

Among ourselves, we’d call the people there ‘nutters’, ‘loons’ and worse, the casual cruelty of youth partially excused by masking fear of things we couldn’t possibly understand. I never told my friends that someone from my own family stayed there, and silently wished not to run into her when we went for a kickabout: I still pang with guilt. I used to strobe.

The police said, “You were the last person to see her,” and I wanted to say, “I’m twelve, mate, I don’t really know what you want me to do with that.” They asked, “Did you notice anything out of the ordinary,” and I wanted to say, “If you ever met her, you’d realise that’s a pretty stupid question.” I said, “No.”

It was my first funeral. The man giving the sermon had a booming, commanding voice, his words swirled around, engulfing the beautiful church she loved so dearly. I wondered why he spoke more about Him than her; she was a wonderful painter, and kind, and funny as shit on her good days.

In the archives there is a photograph of a man, his back to the camera, surrounded by empty chairs.10 Isolated and anonymous. To his left, a television switched off. To his right, a window onto the world, so close yet desperately out of his reach. I wonder if he sees his spectral reflection in the dark glow of the television or in the glass which keeps the world from him. I wonder if she ever sat alone in this room with only hazy reflections for company. I wonder if she closed her eyes and pretended to be somewhere, anywhere, else. I hope the room wasn’t always empty for her, that she sat with friends, and talked and laughed about how silly the rest of us could be outside. That the word ‘asylum’ wasn’t on anyone’s lips and maybe being a part of recorded history wasn’t always so heavy.

Her memorial card was light. Lighter than the patient record buried somewhere in an archive.

Swartz, ‘Asylum Case Records,’ p. 289

Swartz, p. 297

John Higgs, I Have America Surrounded: The Life of Timothy Leary (London: Friday Books, 2006), p. 48

Dundee, Dundee University Archives, THB 29/11/2/1

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Dundee, Dundee University Archives, THB 29/8/6/3/5

Dundee, Dundee University Archives, THB 29/8/6/4/2

I Know What You Did Last Summer, dir. by Jim Gillespie, (Columbia Pictures, 1997) [Motion Picture]

Urban Legend, dir. by Jamie Blanks, (Sony Pictures, 1998) [Motion Picture]

Dundee, Dundee University Archives, THB 29/15/1/2/2/6